Craft Traditions: A Permanent Collection

CRAFT TRADITIONS: A Permanent Collection

Walk through our permanent collection of archived, Appalachian craft. This exhibit of approximately 250 works features woodcarving, textiles, furniture, basketry, pottery, dolls, and other crafts of Southern Appalachia, dating from 1855 to the late 20th century.

Craft Traditions:

The Southern Highland Craft Guild Collection

An ongoing exhibition

The Southern Highland Craft Guild Collection represents the historical crafts of southern Appalachia. Many pieces date from the 19th century and were collected in the Asheville area by Frances L. Goodrich, a founding member of the Guild. Goodrich came to the region in 1890 to do educational and organizational work as a volunteer for the Presbyterian Home Mission Board. She had not planned to work in the crafts field, but rather, the idea was thrust upon her in the form of an antique bedspread.

Goodrich’s combination of social work, teaching, and family counseling was appreciated by the mountain people she served; however, something was lacking that she described as “healthful excitement.” She was sure that an interest that connected mountain women to the wider world would be beneficial, and if this produced cash, so much the better. As Goodrich tells it, just as she was “pondering the resources at hand for bringing healthful excitement into the lives of her neighbor women, one of them out of pure good will and affection brought to her as a gift a coverlet, forty years old, woven in the Double Bowknot pattern, golden brown on a cream-colored background. The brown had been dyed with chestnut oak, and was as fine a color as the day it was finished…Here was a fine craft, dying out and desirable to revive. Did she hold the clue to her puzzle in her very hand?”

Handweaving was indeed the answer, and Goodrich began to organize mountain women to produce crafts that she would market nationally and regionally. By 1897, she had moved to Allanstand, a community in Madison County’s Laurel Country, where she found the population more generally involved in traditional fiber arts to the extent that they even tended to wear the same hand dyed colors – people said the Laurel folk could be told “by the red.” She called her organization Allanstand Cottage Industries. By 1897, Goodrich had built a log cabin alongside the main road to sell crafts, which was the first Allanstand Craft Shop.

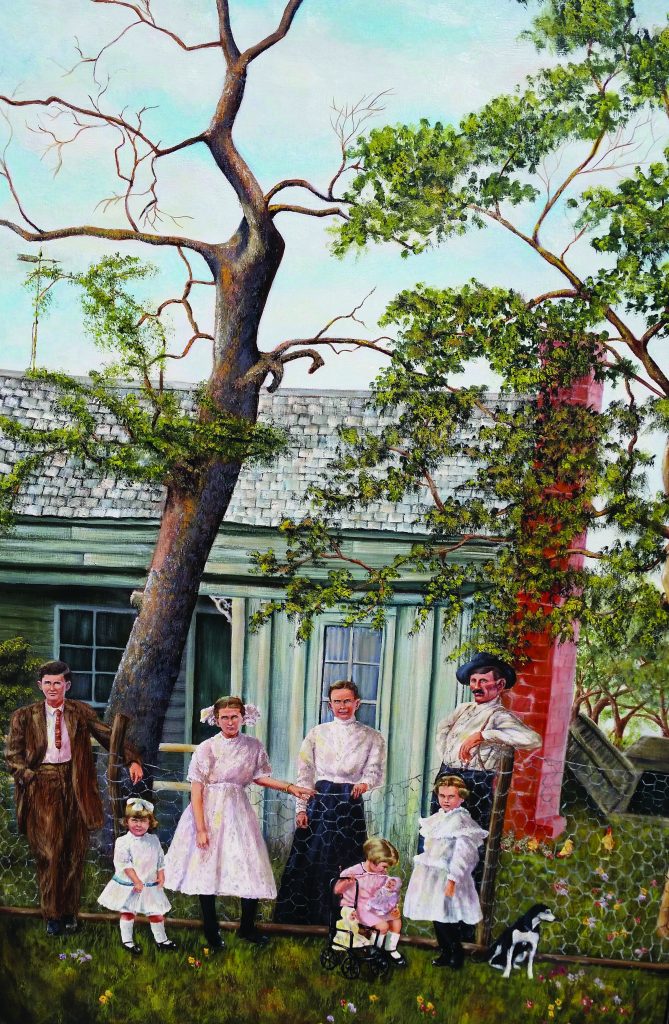

Certainly, traditional mountain crafts were around when Goodrich shone a new light on them in the 1890s. Crafts from the Cherokee, white and black mountaineers were made from necessity and for trade. Mountain families practiced a whole range of traditional skills due to the geographic and economic isolation of the region. A pre-industrial lifestyle survived until the railroad reached Asheville in 1880, where Goodrich found a folk society in proximity to a cosmopolitan city. In mainstream America, domestic weaving was the stuff of grandmother’s day, but Appalachia seemed like a pastoral society to romantic reformers who perceived a home-craft economy as a dignified alternative to modern life and homogenization. Many outsiders came to Appalachia to practice a rural lifestyle. Many native people began to see in the old ways a path to independence, distinction and meaningful work. Because of the stubbornness of some individuals and the forces of relative isolation, traditional craft practice survived in Appalachia to be “discovered” by Frances Goodrich and the modern world.

Beyond the functional and economic importance of crafts, Goodrich had a strong interest in the beauty of good design and sound construction. Such qualities as material heft, color, shape and texture would please the senses, and the maker could find satisfaction in sharing good work and bringing joy to others.

Frances L. Goodrich’s work was part of a larger effort called the Southern Appalachian Handicraft Revival. This movement dates from the late 1800s through the 1930s and included many schools and colleges that used crafts to further educational, social and economic goals. Berea College in Kentucky established a crafts program in the 1890s that evolved into its Student Craft Industries still in operation today. The Pi Beta Phi Fraternity opened a settlement school in Gatlinburg, Tennessee in 1913, which became the present-day Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts. Olive Dame Campbell and Marguerite Butler established John C. Campbell Folk School in 1925 in Brasstown, North Carolina. Founded in 1929 by Lucy Morgan, Penland School of Crafts grew out of the Appalachian School run by the Episcopalian Church at Penland, North Carolina. Today, both the Folk School and Penland are nationally recognized centers of crafts education. These groups and others came together in 1930 to create the Southern Highland Craft Guild, which would serve as an umbrella organization to preserve and promote southern Appalachian crafts.

Goodrich, by then retired, gave Allanstand Cottage Industries to the Guild. This was a great boost to the new organization to count among its assets the first, best-known and highest quality shop in the region. Goodrich also donated her craft collection, which she had begun assembling in the early 1890s. This initial gift formed the core of the Southern Highland Craft Guild Collection.

The Guild Collection includes works from Berea College, Campbell Folk School, Penland School and other centers that have taught craft skills and connected makers to markets throughout the 20th century. These institutions also added their own patterns to the rhythms of mountain life, such as the Friday morning custom of local carvers coming to the Folk School to sell their latest works.

Some objects in the collection seem timeless – a Settin’ Chair is a typical form and craftspeople in these mountains still make them, feeling no need to change anything about the form, material or method. But, makers also responded to the currents of taste and design. Traditional skills of the farm and home were applied to creating items for fashion and modern, even suburban, uses. Though cornshucks were typically used to make floor mats and dolls, shuckweavers added purses and hats to their inventory to appeal to new buyers. They also made their dolls more refined and intricate. Cherokee basketmakers started making wastebaskets, wall-hung mail pockets and purses as a direct result of market forces.

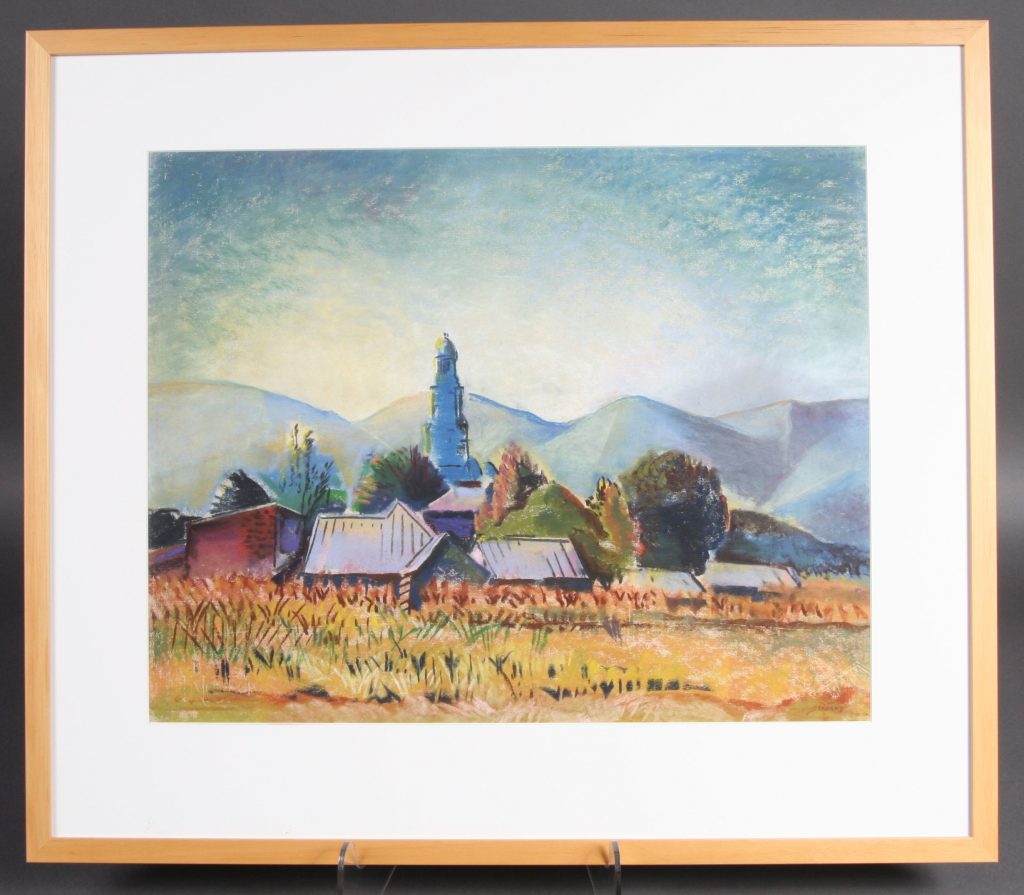

Many craft buyers, even in the 1890s, were travelers or vacationers. As tourism is connected to a sense of place, perhaps the crafts assumed a regional identity. Much work was made that celebrated the supposed old-time character of the mountains and its people’s connection to a frontier-like lifestyle. Both Pisgah Forest Pottery and The Spinning Wheel in Asheville produced ceramics and textiles that featured covered wagons and other pioneer scenes. The log cabin was an important symbol of the Southern Appalachian Handicraft Revival. Allanstand Cottage Industries built a log cabin as the first of its shops. Campbell Folk School’s first building project was a log cabin, and the Penland Weaver’s Cabin was the birthplace of the Southern Highland Craft Guild. The Guild’s official logo for decades pictured a cabin nestled in the mountains. Cabins also decorate many craft objects, such as Fred Smith’s carved wooden tray and Clara Hilton’s ceramic vase. These native designs sometimes had a souvenir quality, and traditional artists often produced “tourist ware,” such as Louise Bigmeat Maney’s Bear Paw Ashtray.

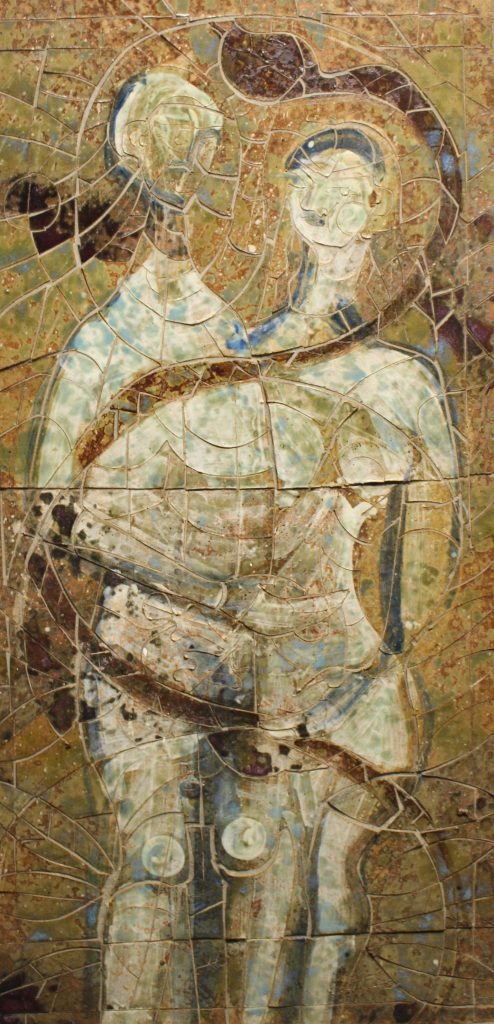

In contrast, the Guild Collection includes strikingly contemporary works that show craftspeople responding to 20th century art movements. Many pieces from the 1930s show the influence of Art Deco and Social Realism, such as Watty Chiltoskey’s stylized horse forms and Tom Brown’s carved figures that resemble those in a WPA mural. Similarly, craftspeople in the 1950s and ‘60s incorporated Modernist imagery into their work, as seen in Charles Counts’ textile designs, Lynn Gault’s ceramic sculptures and Rude Osolnik’s turned candlesticks.

Some works are outwardly traditional, but on closer examination can be seen as highly original. Granny Donaldson’s Cow Blanket was her personal invention, though possibly inspired by an Italian folk blanket used for festival parades. Donaldson used her skills in spinning, dyeing and crocheting to create a new textile form to brighten the wall. Some works are clearly traditional, such as Eva Wolfe’s doublewoven Storage Basket and a rivercane Mat woven by an anonymous Cherokee maker. These 20th century items look for all the world like those sold or bartered to the English in 1700. Some traditions are just so right that they don’t change much.

Like the Cow Blanket, Cordelia Ritchie’s spiral-handled Dream Basket combines traditional making with innovative design. This unique basket represents the Guild well as a logo: in addition to its undeniable beauty, the Dream Basket aptly combines natural materials, traditional skills and personal vision. It is a functional object that could be used to store beans or yarn, but its main purpose is to look good and provide joy and provoke thought and feeling. Some people call this art. Most mountain craftspeople don’t care what you call it, but they know when it is right and good. Creating a world in which craft and other native talents can flourish – this is the Guild’s legacy. The craftspeople of Southern Appalachia are always aware of tradition and forever renewing themselves from the old sources of nature, family, spiritual life and the desire to share one’s gifts with others. They have also made the Southern Highland Craft Guild a creative center of contemporary craft and design that is recognized around the world.

~Jan Davidson

Director, John C. Campbell Folk School

Brasstown, North Carolina